Blind faith goes well with tandoori chicken

Bohras are known for their love for food and for their servility to the clergy. Might there be a connection between the two?

Is it possible to believe in God on an empty stomach? The gut says no. In the absence of food, most believers, especially Bohras, would lose their appetite for all things religious. Doctrinally, food is not a part of their faith, but practically, it might well be. Bohras cannot swallow strictures without food easing the passage. And one can hardly blame them. They need a surfeit of savouries, sweetmeats and other victuals to make the excesses of the priestly class palatable.

Perhaps, the evolution of this process, this complementarity of religion and food, follows a certain logic. Wiley priests figured that the mythology of fire and brimstone was not enough to tame the human mind. Of all the base desires that religion considers evil, gluttony is the least problematic. One could gorge on halal food until the cows come home and yet remain on this side of piety. The result: believers go out of shape physically and, given the state of Bohras, one could argue, even spiritually.

This was all to a plan. Nothing delights a priest more than a misshapen and maladjusted believer. And Bohras, with their umbilical cord tethered to jamat and jaman, are a perfect malleable material. From a young age, they are weaned on the ideological pap that they are the true mumins and the Dai would guarantee their passage to paradise (for a price, of course). With this and other similar deceptions, Bohra clerics have successfully fashioned a community that practically eats out of their hands.

But despite their complete subjugation and servility, it is not that Bohras cannot bleat an opinion. When they complained about how fat and ugly they had become, the priests lent a sympathetic ear and came up with an ingenious solution. They gave people tents to wear so that they could cover their corpulent bodies. Men were ordered to don plain white oversized tunics, and women printed, colorful two-piece hijabs. Thus, Bohras came to take pride in their well-rounded and well-pitched identity even as they mortgaged their stomachs and souls to the temptations of gluttony.

Wild and free

Ask a Bohra which food defines their culture, and the invariable answer would be: daal chawal palidu. This simple rice and a lentil-flour soup combination is a staple of every Bohra home, and although it carries the culinary burden of the whole community, it remains a humble and affordable food. But to judge Bohra cuisine by this signature dish would be grossly misleading. The Bohra mind and soul may have been domesticated, but their palate remains wild and free. Or rather, has been calculatedly designed to be wild and free.

In Udaipur, when we were still dipping our measly roti into an apology for a mutton curry, people in Bombay’s Najam Bagh were devouring shahi kormas and chicken tandoori and tender goat meat doused in cashew-white gravy; and while we wiped our hands with a newspaper as the jamatkhana didn’t have running water, they were polishing off ice-creams and halwas, burping with satisfaction, and going to bed with a dose of Digene. Small towns like Udaipur were not yet exposed to the culinary feasts of big cities like Bombay. There, the cooks, the bhatiyaraas, stirred magic into every exotic dish they made, while we in the hinterland suffered the same old laddu, gosht, roti and pulao routine.

Our food was meh, to put it mildly. It could be argued that the reformists in Udaipur rebelled against the priestly class because we were bored out of our minds eating the meagre and monochromatic food for years on end. If we had a chance to relish the magic of Bombay delicacies, we might today be licking the priestly toes, no doubt, like the rest of the Bohra brethren. Alas, the notions of dignity and freedom reached our minds first.

But dignity and freedom do not a fine dish make. For years, even after the reformist rebellion, our jamatkahna and our kitchens were stuck in a culinary rut—cooking the same blasé fare. The food was simple, relatively healthy, but stubbornly lacking in variety. With time, as Udaipur Bohras came into money—thanks to remittances from Gulf countries, education and upward social mobility and the opening up of the Indian economy—their prosperity came to be reflected in their food. Community meals became more numerous, and the menu more exciting. These days, chilli chicken, mutton biryani, anjeer halwa, ice-cream and the like are commonplace, but that sublime Bombay taste still eludes us.

In our kitchens, we continue to remain prosaic, using the same mandatory masalas for meats, fish and vegetables and anything else that might show up on the kitchen counter. And of course, our meat-centric bias dictates that we show no mercy to vegetables—we overcook the daylights out of them. Daal is scorned with a passion. Our palidu is deprived of drumsticks, and our kadi has yet to make an acquaintance with kadi patta. We still cannot tell kadi from kaadhi, and dabba gosht for us is gosht in a dabba. Samosas (of the meat variety) are a rarity reserved for guests and special occasions. Our haleem has yet to crossover into the realm of khichda which we anyway consider as a transgendered khichdi, and korma for us is karmo with an identity crisis. Nihari, saat-handi paya, mutton roast, lagan seekh (with a green garlic tadka) and many such treats are still beyond our pale. In short, we may be the granddaddy of the reform movement, but when it comes to fine food, we are still cutting milk teeth.

Classic dichotomy

Other small towns probably also share Udaipur’s culinary backwardness—a classic dichotomy between the centre and the periphery. The centre is, of course, Bombay, capital of Bohra cuisine and the seat of the Dawat—the priestly establishment. This is no coincidence. Culture has a habit of tagging along with power. Under the Mughals, the khansamas in the imperial kitchens experimented with food. Mixing Persian, Turkish and Central Asian influences with local ingredients and recipes, they invented Mughlai Cuisine. The chefs at the famous Karim’s restaurant in Delhi trace their lineage to Emperor Akbar’s kitchen.

Bohra cuisine, however, has no such imperial pedigree, but much of what they have can be attributed to their self-proclaimed royals. The Dai and his extended family lord it over Bohras like latter-day Mughals, claiming divinity, regal pretensions and a fanatical following. The Dawat is their little empire without borders, and within its hypothetical realms, their writ of power, rapacity, arrogance and extravagance rules. Of the many illicit demands they make on the community, the one that takes the cake is the ziyafat—a royal feast hosted by an abde (slave) for the Dai and his entourage.

Ziyafat is an elaborate, lavish affair where every detail is micro-managed by the handlers of the royal family. Bohras, fed-up and harried, have come to call it aafat (trouble) because of the headache and financial drain it brings upon the host. During a ziyafat, the food is a side dish; the main course is always the money. Before the royal consent is given, the host must agree to pay a large (often negotiated) sum. The higher the status of the royal guest, the greater the sum. By condescending to land their regal haunches in your living room, they are blessing your home, and in return, you must scrape and bow, kiss their feet, and shower them with cash (Cheques they cannot digest). And throw in fine food for good measure.

Hate or envy them if you must, but the priests’ love for gourmet food is perhaps their only redeeming quality. Bohra cuisine has developed and evolved mainly due to the ziyafat business and the accompanying efforts to please the priestly palate. Over the last century, Bohras from small towns and cities emigrating to Mumbai brought with them their recipes and passion for food. The commingling and contesting influences of the Suratis, Kathiawaris, Kapadwanjis, Dahodis, and so many others resulted in what has come to be known as Bohra cuisine. But despite its richness and variety, the secrets of recipes exist only in the heads of women and the bhatiyaras. Like much of their Ismaili esoteric doctrine, it remains hidden. There is no formal, organised compilation of Bohra recipes, nor the documentation of the culture, history and ethnography of their food.

There is one popular recipe book with a stunningly original title, Daal Chawaal Palidu. If anything, the book is a thin gruel, a bland list of ingredients and methods. It seems the author treated it like a cooking chore and was in a hurry to finish it. Bohras, of course, can do better and deserve better. They deserve a recipe book to match their fantastic culinary heritage. What they need is a Bohra Madhur Jaffery or a Julia Child.

Table manners

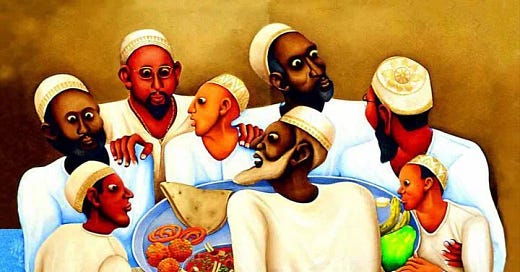

They also need table manners, or shall we say, thaal manners? The thaal is a large platter around which they sit and eat, and this is hardly the place to flaunt one’s etiquette in fine dining. Eating from the same plate, digging fingers into the same dish, sharing spoons, etc., doesn’t allow manners or hygiene much of an elbow room. The most you could do is eat daintily with the tips of your fingers, keep a separate spoon, if available; if not, you forgo the delicacy or quickly put the food in your mouth without your fingers touching your tongue and lips, and without anyone noticing you. You have to be furtive lest you’re caught. And if you’re caught, be prepared to be shamed for being snooty.

Of course, the thaal has its merits: It is economical and efficient, there is practically no wastage of food, washing up and other logistics are easy; it promotes camaraderie and social bonding. It is a great social leveller—and above all, it is a custom that has the weight of tradition and religion behind it. The Bohras, for better or worse, are stuck with the thaal as they are with their parasitic clergy.

Although food is integral to human survival, for Bohras—reformist or orthodox—it boils down to much more. Food binds us together, brings us together. In fact, faith would have little currency without that inevitable meal. Food, and the expectation of it, helps one endure those dreary majalises. And for the orthodox brethren, for whom no gathering, religious or otherwise, can end without the ritual of chest-beating, that expectation could not be sweeter.

And for us reformists in Udaipur, we continue to wait outside our jamatkhana ready for another bout of communal eating—eager to mix roti, rice and curry in the middle of the thaal, and wolf it down without a care. These days, with heightened hygiene sensibilities, some of us draw our portion of food to our side of the thaal—and there is a small satisfaction that when we finish, we have taps to wash our hands. Still, we are hard pressed to find soap or a napkin. But what is not hard to find is dignity and a straight spine.

Nice read Shaukat Bhai. Bohras from Udaipur will identify with it. I liked the 'covered them with tents...to cover their corpulent bodies...'. Deen and Dinner go together for us. The 'Urban Bank AGM' is called the 'Urban Bank nu Dinner'... but we love our community as much as humble and innocent they are. I remember being in the masjid at Deira in Dubai on my first Ashoora. The sound and agony of the frenzied 'maatam' on dasmi raat suddenly came to a stand still and was replaced by the mumins clamoring for their 'thaal' as soon as it was announced that food is being served. I could not believe that emotions could change color so quickly... in the blink of an eye.

Once again... nice read.

Haha - “korma for us is karmo with an identity crisis” fun read!

“In our kitchens, we continue to remain prosaic, using the same mandatory masalas for meats, fish and vegetables and anything else that might show up on the kitchen counter.” - so true, that would be me 🙂

I have the book - Daal chawal palidu - bought it so I could pass on Bohra cuisine tricks to my kids - wishful thinking!